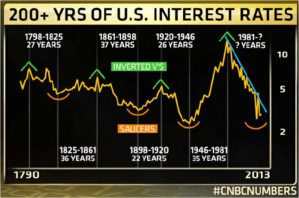

My Comments: Interest rates are the price paid for using money owned by someone else. The rise and fall of that price, which we call interest, is a critical element when it comes to deciding how your money should be invested. For over 30 years they have been trending down and you will soon see that trend reversed. Being prepared will result in greater financial freedom for you.

My Comments: Interest rates are the price paid for using money owned by someone else. The rise and fall of that price, which we call interest, is a critical element when it comes to deciding how your money should be invested. For over 30 years they have been trending down and you will soon see that trend reversed. Being prepared will result in greater financial freedom for you.

By Scott Minerd, Chairman of Investments, Guggenheim Partners

As appeared in the Financial Times global print edition, July 16, 2015

In 1898, Swedish economist Knut Wicksell argued that there existed a “natural” rate of interest that balanced the supply and demand of credit, assuring the appropriate allocation of saving and investment.

Should market interest rates remain below the natural rate for an extended period, investors will borrow excessively, allocating capital into less productive investments, and ultimately into purely speculative ones.

This is what the US economy faces today after years of meagre borrowing costs. Policymakers have created a Wicksellian dilemma where investment spurred by low interest rates is driving economic growth, but these inefficient investments support growth at the expense of lower productivity in the economy.

In recent years, this investment has flowed into housing, commercial real estate, and equities, driving asset prices higher, exactly the goal of the Federal Reserve in the wake of the financial crisis. But as the recovery in real estate and equities matures, a darker side of this imbalance between natural and market rates is beginning to emerge. Many investments today using artificially cheap capital are not increasing productivity – they are being made, because money is cheap and the profit motive is strong.

Consider the evidence. This year likely will witness record US stock buybacks; the second biggest year for mergers and acquisitions; the highest percentage of non-investment grade borrowers among new issuers of corporate debt; and a record for covenant-light loan issuance.

In the midst of all this, stock prices are appreciating at the slowest pace since the financial crisis. Why? Because top-line growth is low and productive investments in core businesses are wanton.

Over time, the natural rate of interest should roughly equate to the average return on new capital investment. Distortions in economic activity begin to occur when the natural rate varies materially from the market rate.

The aftermath of the current period of corporate borrowing and splurging will be nasty. Consider that the majority of defaults of US high-yield bonds during 2008 and 2009 were loans originated between 2005 and 2007 – the final three years of the last credit cycle when M&A and leveraged buyouts peaked. Similar to today, credit remained cheap and the Fed was slow to raise interest rates.

We are not back in the frothy days of 2007, but we are leaving the realm of smart investment decisions and moving into the “silly season” when investors become convinced that recession is nowhere on the horizon and market downside is limited.

It is a world where asset prices continue to appreciate and confidence remains strong, while capital chases a shrinking pool of productive investment opportunities. Similar to the run-up to 2007, rising asset prices and malinvestments today may be sowing the seeds of the next financial crisis.

The harsh reality is extended periods of malinvestment result in declining productivity growth, lower potential output, and slower increases in living standards. A failure to normalize market interest rates soon will result in more capital plowed into investments that are less productive and more speculative.

As productivity declines, long-term growth will be stunted. Eventually, inflationary pressures will build, forcing market interest rates to rise. The longer market rates remain below the natural rate the greater the purge will be once higher rates induce a recession, causing a sharp rise in defaults among malinvestments made during the period of cheap credit.

Today looks a lot like 2004 or 2005, when investors were blissfully ignorant of what awaited. It is still early, but I get increasingly concerned the longer I see undisciplined investors clamoring for bonds with suspect credit worthiness at ludicrously low yields. Higher rates, higher prices, or both are on the horizon. Before long, some of those bonds may become toxic waste.

The good news is there remains time to take action. Policymakers can still make adjustments to avoid the worst phase of the credit cycle. To reduce the continued accommodation of these marginal investments, the US central bank should normalize rates soon. For investors, the time has come to consider opportunities to book gains in assets that in the reasonable light of day a prudent investor would never buy.